Jenny Reeder, a member of my cohort here at GMU, was studying for her quals last semester, and she showed me her 3×5 cards.

I’d never really used them before, personally, for anything other than public speaking classes in high school. They don’t really gibe with my rather organic, piecemeal approach to studying or to note taking. It always struck me as an extra activity that would distract me from the actual work at hand. But that’s just me– YMMV, different strokes for different folks, something about drummers, etc.

Now, just because I don’t use them doesn’t mean I’m not fascinated to see them. And Jenny’s were amazing. She had multiple sets in different orders– one stack by author, another in chronological order, and another that was organized alphabetically by theme.

It’s that last stack that really got to me– it was a fascinating way to look at History, where causality, chronology, biography, and historiography all fall by the wayside. Where Reconstruction is nearer to Reformation than it is to the Civil War. Flipping though those cards, I realized, was historical gymnastics. You had to shift modes, books, eras, and patterns with each flip of a card. Explain the House of Burgesses. Okay. Flip the card. Explain HUAC! The sudden shifts and turns didn’t just make practicing for quals more challenging, they made it more engaging and fun.

* * *

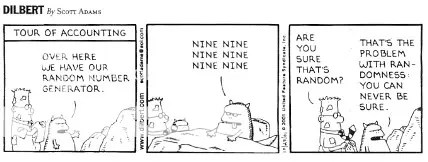

If you have an iPod, you’ve had those moments where you suspect that the “shuffle” feature isn’t as random as it’s supposed to be– why else would it play three songs in a row from the 1980s that all feature former Beatles? But, as this NPR report and this episode of WGBH’s Open Source make pretty clear, it’s not that the iPod isn’t random– it’s that our minds are quite bad at perceiving randomness. We naturally and instinctively look for order, for patterns, and our mind gloms onto them instantly, even if what we’re really looking at is completely random…

Even in the face of chaos, our brains look for order, looking for connections, perceiving causality. And that process is a lot of what we as historians do– we look to the chaos of the past, and try to make order of it. Sometimes we do it by imposing our own frameworks onto the events of the past, but we at least like to think that what we are actually doing is illuminating connections that may have been obscured, perceiving the organic order where it may look like chaos or disorder.

So how do we harness this propensity to see order, and make it work for us?

* * *

It seems to me that randomness has traditionally been a bit of an anathema to historians. The sheer vastness of history itself requires the imposition of order, and that’s the historian’s task. “Doing history” is making order out of disorder. Why would we embrace the chaos?

But digital tools allow us to work with things differently. This started to be apparent with the New Social History, with historians working with punch-card computers to crunch number sets so vast that they had been useless before. Computers are great for making large data sets manageable.

They’re also quite good as pseudorandom number generators, which in turn means that they are quite good at creating fairly random juxtapositions. We can see this with the iPod’s shuffle feature, or even the link on Wikipedia that takes you to a random page. We now find ourselves in a age of shuffle, where wild juxtaposition is the norm.

Even simple little applications like the Random Activity Generator can be powerful tools for promoting creative thinking. Incorporating the principle of randomness into tools for digital humanists would, I think, help promote better scholarship. Shuffling– creating random juxtapositions– forces the mind to make connections between otherwise unconnected items. And finding new connections between historical events– isn’t that at the heart of a historian’s work?